This website [external link] is a short and sweet display of American Sign Language in Canada. You will find information on ASL’s history in Canada, ASL’s current status in the country, information on ASL’s linguistic profile, as well as community resources for the language in Canada.

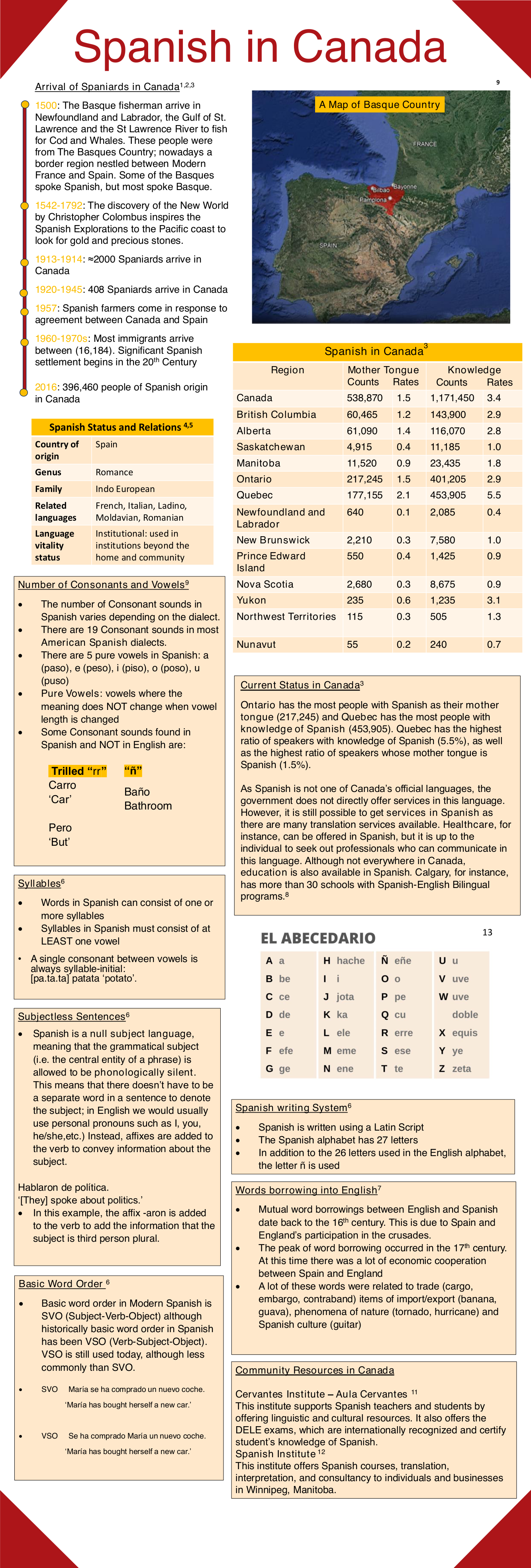

Heritage Languages of Canada: Spanish

This infographic explores the history of the Spanish language in Canada, investigating the immigration of Spanish speakers. Italso provides an overview the number and distribution of speakers, a linguistic profile, and a compilation of community resources of the Spanish language community in Canada.

References

1 Anderson, G.M. & Cazorla-Sánchez, A. (2008.) Spanish Canadians. The Canadian Encyclopedia. https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/spanish

2 NL History. (2016). Basques in Newfoundland. Newfoundland and Labrador History. https://www.nlhistory.ca/basques-innewfoundland/

3 Statistics Canada. 2023. (table). Census Profile. 2021 Census of Population. Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-316-X2021001. Ottawa. Released March 29, 2023.

4 Dryer, Matthew S. & Haspelmath, Martin (eds.) (2013.) The World Atlas of Language Structures Online. Leipzig: Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology. https://wals.info

5 Eberhard, David M., Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig (eds.). 2023. Ethnologue: Languages of the World. Twentysixth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com

6 Mackenzie, I. (1999-2022). The Linguistics of Spanish. Retrieved from https://www.staff.ncl.ac.uk/i.e.mackenzie/index.html

7 Ismagilova, A. R., & Palutina, O. G. (2017). Mutual Word Borrowings between the English and the Spanish Languages. Journal of History Culture and Art Research, 6(4), 571-579. https://doi.org/10.7596/taksad.v6i4.1149

8 The World Learns Spanish. (2020). https://www.educacionyfp.gob.es/canada/en_CA/dam/jcr:c06c3a1f-ac39-4b34-92a8-ad3e3809a975/emee-2020-08-caning.pdf.

9 Silva Valencia, J.C. (2022). A Comparative Linguistic Analysis of English and Spanish Phonological System. GIST – Education and Learning Research Journal, 25, 140-156. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.1152

10 Heroes and Legends Documentary Channel. (2023, April 16). Vikings, Basques, and the Fishermen who Changed the World [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xxyuiZeHWq0

11 Instituto Cervantes and the Aula Cervantes. (n.d.). University of Calgary. Retrieved November 10, 2023, from

https://arts.ucalgary.ca/languages-linguistics-literatures-cultures/spanish/home/programs-andresources/resources/instituto-cervantes-and-aula-cervantes

12 Spanish Institute – home. (2010). https://www.spanishinstitute.ca/

13 Spanish With Tati. (n.d.). Spanish Alphabet Pronunciation. Retrieved November 8, 2023, from https://spanishwithtati.com/spanish-alphabet-pronunciation/

Word on the Street: Genetic? Phonetic? I just don’t get it!

What makes a dialect stick around?

This podcast episode ventures to learn a bit about how we learn (or unlearn) dialect, and how that sometimes carries through parents and children.

References

Brown, Vivian R. Evolution of the Merger of /I/ and /ε/ before Nasals in Tennessee. American Speech, Vol. 66, No. 3 (Autumn, 1991), pp. 303-315

Chambers, J. K. (1992). Dialect acquisition. Language, 68(4), 673-705.

Chambers, J. K. (2002). Dynamics of dialect convergence. Journal of Sociolinguistics, 6(1), 121-123.

Accents in ASL

Learn about accents in American Sign Language (ASL) and the many factors that contribute to these variations. There will be video clip examples. Maybe you’ll even learn something new!

References

ASL Connect. (2021, January 15) Birthday Variants. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ExwLJIWP-xE

ASLized!. (2013, June 17) Deaf Schools (with audio and captions). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mkwYHheJQVw

Cheng, K. (2021, July 6). Deaf culture: Sign language “accents” or “styles”: Start ASL. Start ASL. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.startasl.com/sign-language-accents-or-styles/

Contreras, R. (2002). Regional, Cultural, and Sociolinguistic Variation of ASL in the United States. ASL Linguistics: Sociolinguistic Variation of ASL. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/pages-layout/sociolinguisticvariationofasl.htm

Fessenden, M. (2015, December 4). There’s A philly sign language accent. Smithsonian.com. Retrieved March 1, 2023, from https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/theres-philly-sign-language-accent-180957459/

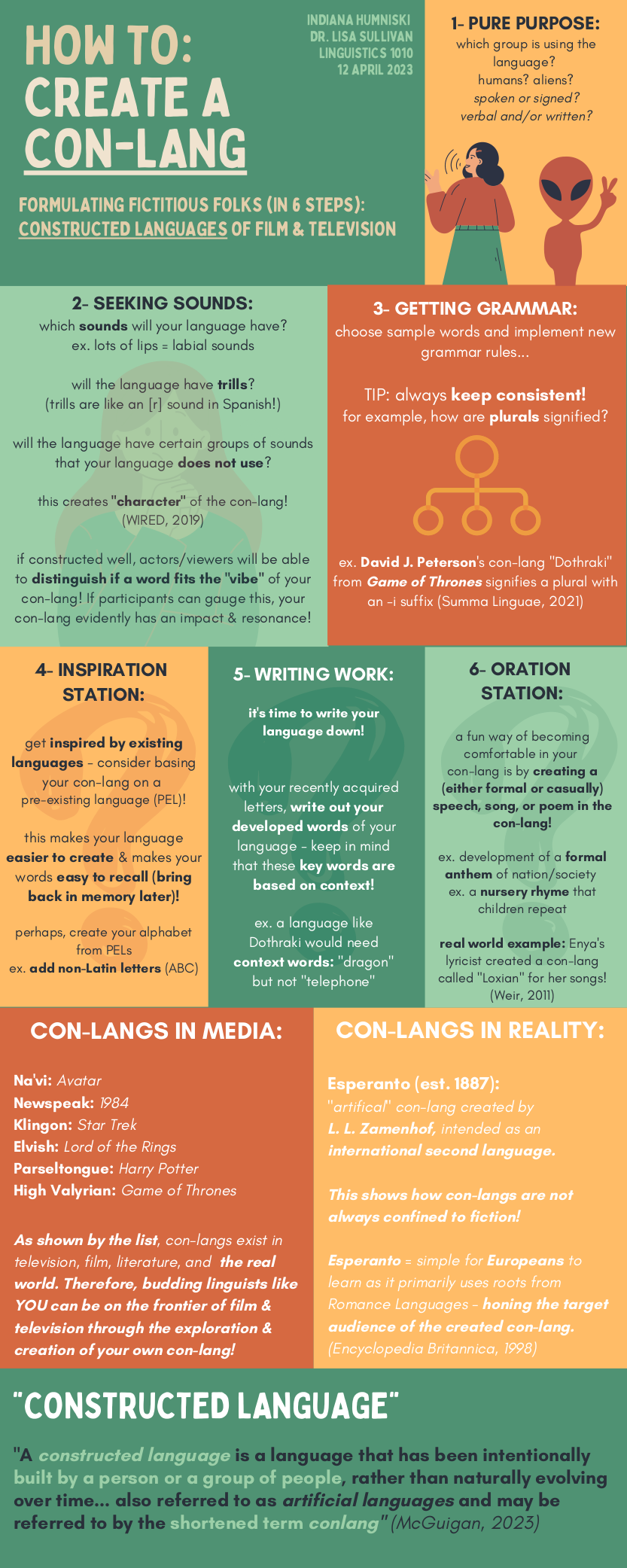

How to: Create a Con-lang

This infographic is a how-to guide that showcases a six-step-approach to creating your own constructed language (con-lang) that is applicable to film/television/media.

References

A Complete Guide to Creating a New Language. (2021, March 2). Summa Linguae. https://summalinguae.com/language-culture/guide-creating-new-language/

Babbel. (2019). “Invented Languages: 9 Beloved Conlangs From Pop Culture”. Babbel Magazine. https://www.babbel.com/en/magazine/pop-culture-conlangs

Esperanto | Britannica. (2023). Encyclopedia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/topic/Esperanto/additional-info#history

McGuigan, B. “What is a Constructed Language?” (2023, March 10). Language Humanities. https://www.languagehumanities.org/what-is-a-constructed-language.htm

Weir, W. “From Mystical Nuns to Sigur Rós, the Best Songs in Invented Languages”. (2011). Slate. http://www.slate.com/blogs/browbeat/2011/11/29/invented_languages_in_music_a_brief_history

WIRED. “How to Create a Language: Dothraki Inventor Explains | WIRED.” YouTube, 18 May 2019, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vDD7bQTbVsk&ab_channel=WIRED. Accessed 24 Feb. 2023.

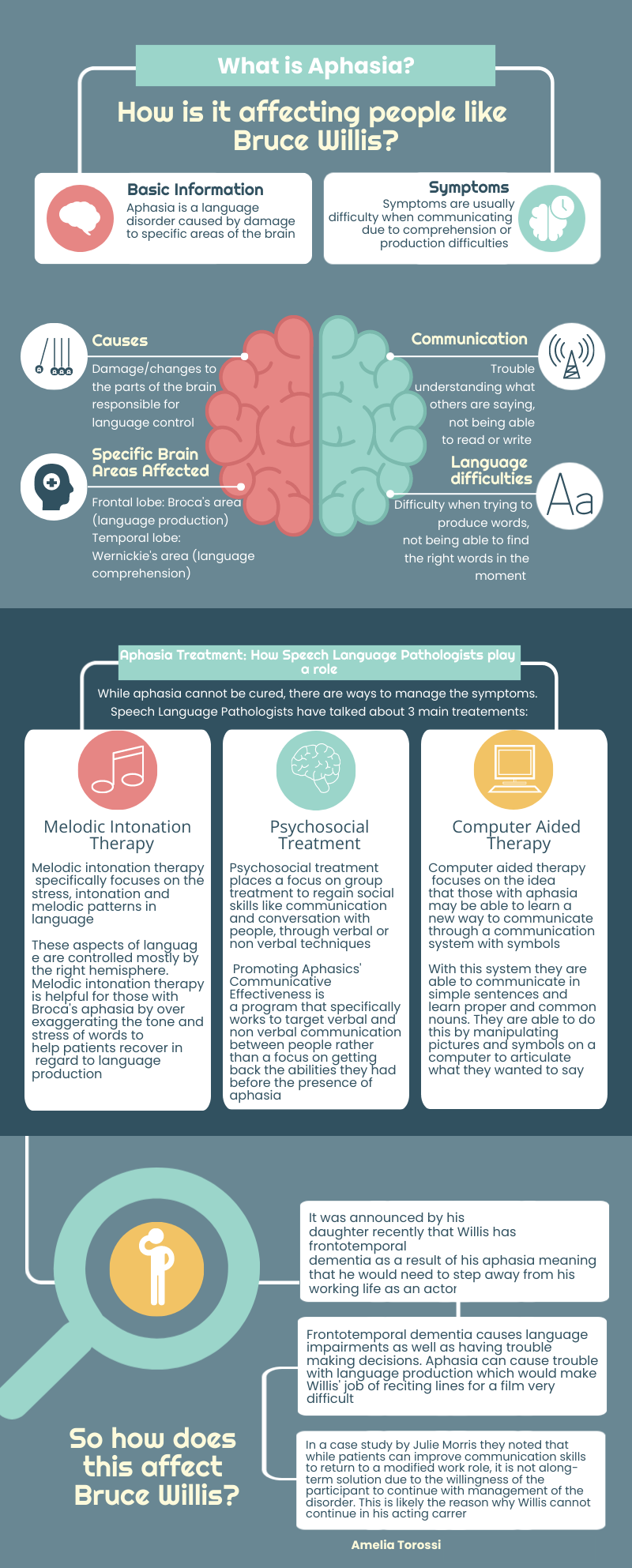

What is Aphasia? How is it affecting people like Bruce Willis?

This infographic explains the symptoms and causes of aphasia, how aphasia affects people that have it, different therapies and treatment methods, and how Bruce Willis’s aphasia diagnosis is affecting him and his life.

References

Abert, M.L. (1998). Treatment of aphasia. Arch Neurol, 55(11), 1417-1419. https://doi.org/10.1001/archneur.55.11.1417

Baker, C., Foster, A. (2022, March 31). What is aphasia, the condition Bruce Willis lives with?. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/what-is-aphasia-the-condition-bruce-willis-lives-with-180399

Loveday, C. (2023, February 20). Bruce Willis has frontotemporal dementia – here’s what we know about the disease. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/bruce-willis-has-frontotemporal-dementia-heres-what-we-know-about-the-disease-200188

Morris, J. (2010). Returning to work with aphasia: A case study. Aphasiology, 25(8), 890-907. https://doi.org/10.1080/02687038.2010.549568

It’s on the tip of my tongue! —is tip of the tongue state just a problem with word processing or also a handy excuse to stave off embarrassment?

Have you ever been about to say something, but for some reason your mind blanked and you couldn’t quite think of the word you wanted to use? That annoying feeling of being so close to knowing what the word you want is but not quite being able to access it actually has a name. It is perhaps unsurprisingly called tip of the tongue state.

What is tip of the tongue state?

Given the common expression “it’s on the tip of my tongue,” tip of the tongue state—also known to linguists as TOT state—is exactly what you’d expect. It is a phenomenon where you know that you know a word, can even visualize how long it is, how many syllables it has, and often the first letter, but for whatever reason you just can’t access the word itself (Rousseau, 2021).

Of course, that’s all well and good, but why do our memories fail us in this way? What does this phenomenon tell us about the way our brains process language?

What does tip of the tongue state tell us about language processing?

Tip of the tongue state supports the idea that before we can actually say a word, there are two stages that are happening in our minds faster than we realize:

- Accessing the meaning of a word. It makes sense that this comes first because when we’re talking, before we can say anything, we need to figure out on a more abstract level what ideas we want to get across

- Accessing the sounds that make up that word. At this stage our brains have matched the ideas we want to get across with corresponding words. All we have to do now is figure out what sounds are associated with the words we want to say so that they come out of our mouths properly when we’re talking

The occurrence of TOT seems to indicate that sometimes something goes wrong when trying to get from stage one to stage two. This processing interruption leads us to have something “on the tip of our tongues” because we know there’s a word to say what we’re thinking, but something is preventing us from being able to produce the actual sounds to get the word out (Sullivan, 2022).

Interestingly, studies also show that this phenomenon affects different groups of people differently. For example, studies have found that people who are bilingual experience more TOTs than people who only speak one language. Researchers think that this might be because bilingual people have less experience with each language they know individually and have the vocabularies of two languages to mentally sort through, which may lead them to get stuck more often in stage two (Gollan et al., 2006).

In addition to different types of people like bilinguals having assorted experiences with TOT, this phenomenon can also be felt differently if you find yourself in a group of people instead of alone.

Can your friend give you TOT?

Have you ever been in a situation where someone is struggling to think of a word or a name, but when they ask your help to try and remember it you find yourself in the same boat? Well, there is research that shows people are more likely to experience TOT state in a group than by themselves (Rousseau, 2021; Rousseau & Kashur, 2021). When you are in a group, there are more factors at play that may increase the possibility you will experience a tip of the tongue state over when you are alone (Rousseau & Kashur, 2021).

For example, what the people in your group say and do might spread their TOT to you. In this case, the tip of the tongue state would arise from something called social contagion. Basically, because someone asked, “what is that word?” or you unconsciously noticed something in their facial expression or other body language that lets you know they have TOT, you now find yourself experiencing the same temporary gap in your memory that they are; you’ve caught tip of the tongue state from them (Rousseau & Kashur, 2021).

It is also possible that being in a group might influence you in other inconspicuous and unconscious ways. In groups, people are likely to think with a “more heads are better than one” mentality. This mindset makes people think that the word is close to being remembered…at least by someone. Unfortunately, this assumption also seems to trigger TOT states more frequently (Rousseau & Kashur, 2021). Regardless of how it happens though, it’s safe to say that the presence of other people does affect your experiences with TOT. Now your only question left about TOT should be, why is this important?

TLDR—What’s the takeaway?

Okay, so now you know that tip of the tongue state is the feeling you get when you know what you want to say but your brain just can’t get the sounds out, and that if you get it while you’re with a friend you might be able to blame them for “contaminating” you with it. It is also important to remember that tip of the togue state is a totally normal phenomenon to experience—enduring an annoying TOT state every once in a while doesn’t mean that you have a bad memory or a problem with how your brain analyzes language, it’s something that happens to everyone.

TOTs actually serve us well during social situations in our everyday lives. For instance, if someone asks you a question that you can’t immediately answer, being able to say that something is “on the tip of your tongue” allows you to show that you’re smart and that you know the answer even if you can’t display it at the present moment. Or what about that awful situation where you should remember a name or a date that won’t quite come to you? You can blame it on TOT to save yourself the embarrassment of admitting you don’t know (Rousseau & Kashur, 2021)!

References

Gollan, T. H., Brown, A. S. & Lindsay, D. S. (2006). From tip-of-the-tongue (TOT) data to theoretical implications in two steps: When more TOTs means better retrieval. Journal of Experimental Psychology. General, 135(3), 462–483. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.135.3.462

Rousseau, L. (2021, August 19). That ‘tip-of-the-tongue’ feeling when a memory is elusive is more likely to happen in groups. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/that-tip-of-the-tongue-feeling-when-a-memory-is-elusive-is-more-likely-to-happen-in-groups-165146

Rousseau, L. & Kashur, N. (2021). Socially shared feelings of imminent recall: More tip-of-the-tongue states are experienced in small groups. Front. Psychol. 12:704433. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2021.704433

Sullivan, L. (2022). JLP 374 Psychology of Language Lecture 6: Production I. [PowerPoint Slides].

How Much Does Your Name Really Say About You?

We all have a name – in fact, you read mine before clicking on my blog post, and an image of who I am almost certainly (and automatically) was generated in your mind. Based on my name, you had probably already assigned me a gender, age, race, ethnicity, and potentially even guessed at my education level and income. You likely predicted a few things right, but you also may have guessed some things wrong. Although these quick assumptions are useful in our busy lives, they can also be misleading and harmful. This is because the clues that a name gives us are based on general patterns, not absolutes (Anderson et al., 2022). Creating strict categories in our minds, including those for names, simplifies many aspects of our lives but can also perpetuate *stereotypes and *discrimination.

The process described above, where you automatically pictured who I was from my name, is a normal process that our mind’s go through when we hear a name. This is because our names are closely tied to who we are, including which social categories we belong to (examples: gender, age, ethnicity, race, education, and income). However, when we start associating names with social categories, in particular those related to race and ethnicity, we can run into trouble. If a landlord receives a stack of applications from people who want to live in their apartment complex, they are going to start inferring who the applicants are based on the names at the top. Without even reading the next lines, they have assigned social categories to each name.

Names and Housing Discrimination

We know that this phenomenon exists thanks to a method called a *matched-guise study. This kind of study allows researchers to determine people’s attitudes towards different social groups in a covert way – that is, without the participants having to directly state their beliefs. To do this, researchers choose a *stimulus, which in this case, would be a tenant application. Landlords are presented with identical applications, with the only change being the *guise. The guise is the factor we think will influence how people respond to the stimulus and therefore reveal their attitudes and beliefs. Since we want to know about the landlord’s judgements regarding names, the guise in this study would be the name at the top of the application. If there is a difference in which applications the landlords are choosing, it must be based on the name on the application. Social science research has confirmed that landlords do make guesses about people’s identities based on their names (Oreopoulous, 2011).

Unfortunately, these guesses are used to discriminate against certain groups of people. Researchers named Hogan and Berry performed an experiment similar to the one described above. They found that Black and Arabic named applications faced barriers that White and Jewish named applicants did not. Those with Black and Arabic names faced discrimination including not getting responses from landlords and facing additional rental conditions (Hogan & Berry, 2011).

Why Does This Matter?

So, what can you take away from this blog post, and how does it apply to your life? I think that although language discrimination can seem like big, scary mountain that is impossible to overcome, it is important that we make small change. If everyone who reads this blog post walks away today with a more inclusive mindset, we have already chipped away at that mountain. The next time you hear a name for the first time, I want you to stop and question that automatic image that pops into your head. Although it is an assumption, it is not certain. We cannot make accurate judgements about people simply based on their names. Although it may sound cliché, the concept of not judging a book by it’s cover is useful here. Our names do say a lot about us, but they certainly do not tell us the whole story.

Definitions

*Stereotype – the automatic characteristics that society attributes to a specific group. Stereotypes are widely held (i.e., believed by most people) and can be harmful.

*Discrimination – unfair treatment of certain groups of people based on social differences such as gender, ethnicity, or race. Stereotypes can be used as a basis for discrimination.

*Matched-guise study – a study where language attitudes and beliefs are indirectly/covertly revealed.

*Stimulus – The object of the study which is presented to the participants. In a matched-guise study, the stimulus (e.g., tenant application) is held constant.

*Guise – The guise is the factor we think will influence how people respond to the stimulus and therefore reveal their attitudes and beliefs. In the experiment above, the guise was the name on the tenant application.

References

Anderson, C., Bjorkman, B., Denis, D., Doner, J., Grant, M., Sanders, N., & Taniguchi, Ai (2022). Language, Power, and Privilege. Essentials of Linguistics, 2nd Edition, (pp. 45- 49). eCampusOntario.

Hogan, B., & Berry, B. (2011). Racial and Ethnic Biases in Rental Housing: An Audit Study of Online Apartment Listings. City & Community, 10(4), 351–372.

Oreopoulous, P (2011). Why Do Skilled Immigrants Struggle in the Labor Market? A Field Experiment with Thirteen Thousand Resumes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3(4), 148-171.

Sanders, N (2021). Language-Based Biases in Legal Contexts. Invited webinar for ezCPD.ca. [ video (59m13s) ] [ PDF (slides) ]

Soffia Fridfinnson is a 4th year undergraduate student at the University of Manitoba. She is majoring in linguistics and minoring in biology. In particular, she enjoys learning about communication disorders and sociolinguistics. Outside of school she likes to work on jigsaw puzzles, read, and spend time outside.

Soffia Fridfinnson is a 4th year undergraduate student at the University of Manitoba. She is majoring in linguistics and minoring in biology. In particular, she enjoys learning about communication disorders and sociolinguistics. Outside of school she likes to work on jigsaw puzzles, read, and spend time outside. Nevada Mogan is a 4th year undergraduate student at University of Manitoba majoring in Linguistics. She is interested in the study and treatment of motor speech disorders. She enjoys live music, travel and reading.

Nevada Mogan is a 4th year undergraduate student at University of Manitoba majoring in Linguistics. She is interested in the study and treatment of motor speech disorders. She enjoys live music, travel and reading.

Indiana Humniski is a 2nd year student, majoring in English and soon-to-transfer into the Honours stream. Indiana has taken a keen interest in learning more about linguistics since taking “Language and Gender” in her first year of university with Dr. Loureiro-Rodriguez at the University of Manitoba. Her idea sparked when watching James Cameron’s sequel to Avatar, where the constructed-language of Na’vi takes centre stage. Outside of class, Indiana enjoys casual analysis of the lyrics of Taylor Swift and boygenius, working her way through classic literature, and taking walks with her campus friends.

Indiana Humniski is a 2nd year student, majoring in English and soon-to-transfer into the Honours stream. Indiana has taken a keen interest in learning more about linguistics since taking “Language and Gender” in her first year of university with Dr. Loureiro-Rodriguez at the University of Manitoba. Her idea sparked when watching James Cameron’s sequel to Avatar, where the constructed-language of Na’vi takes centre stage. Outside of class, Indiana enjoys casual analysis of the lyrics of Taylor Swift and boygenius, working her way through classic literature, and taking walks with her campus friends.

Maggy is a second-year undergraduate student at the University of Manitoba. She is currently studying psychology, but is also interested in the field of linguistics, particularly how language works in the brain. Her other interests include thrift shopping, tap dancing, and curling.

Maggy is a second-year undergraduate student at the University of Manitoba. She is currently studying psychology, but is also interested in the field of linguistics, particularly how language works in the brain. Her other interests include thrift shopping, tap dancing, and curling.